Imitation Kills Originality

How to break free from comparison and create on your own terms

Ever since my fiancé shared René Girard’s concept of “mimetic desire” with me, the idea that we desire things because others desire them, I started noticing it everywhere.

It explains why our culture is experiencing an overload of noise. We rely so heavily on distraction to quiet the anxieties underneath, losing the muscle to pause and ask what we truly want. Instead, we flock to whatever’s next simply because others are flocking there too.

Right now, the pop charts and TikTok’s trending sounds have merged into one feedback loop. Trending sounds often become charting songs. Charting songs then become what artists copy. Throw AI music into the mix, and originality becomes harder to protect.

I’ve felt this pull too. When I shifted from musician/recording engineer to running my own artist service company, I caught myself chasing other companies’ vanity metrics: follower counts, engagement rates. My actual purpose is to help artists create something truly theirs. The number of clients doesn’t matter. The work does.

Here’s the thing: the charts were never designed to measure artistic truth.

So let’s go deeper than trends. Let’s talk about the human psychology behind why we create, chase, compare, and aspire. A philosophical angle, but one that directly shapes how artists move through the modern industry.

Who Was René Girard?

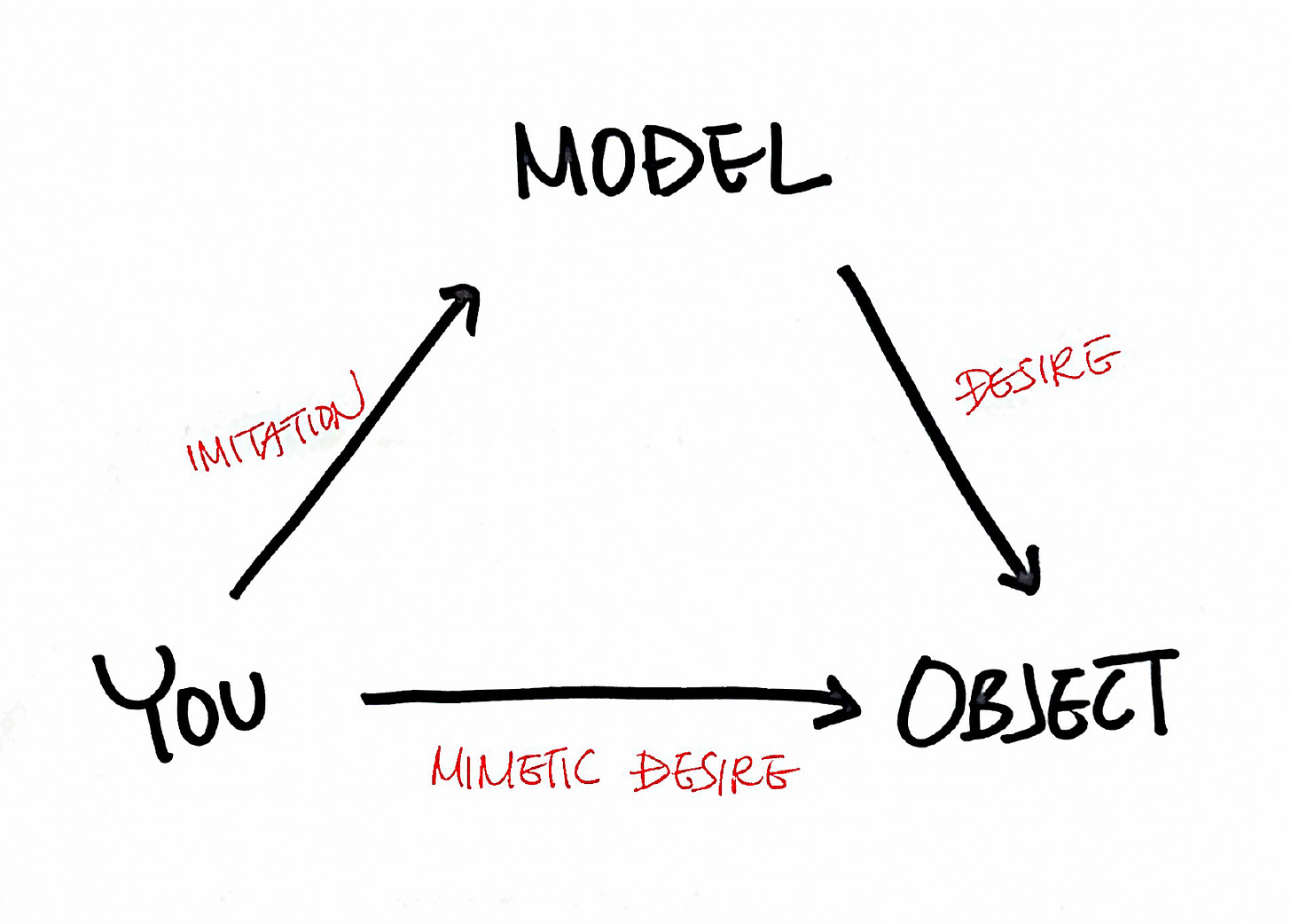

René Girard was a French philosopher and cultural theorist known for developing mimetic theory: the idea that human desire is shaped by imitation rather arising independently

His central question was simple yet profound: Why do we want the things we want?

Girard argued that we rarely desire things on our own. We learn what to desire by watching what others desire, creating a triangular dynamic between the person desiring (you), the person you’re imitating (model), and the thing being desired (object).

Mimetic Desire in Music

So, how does this theory relate to the music industry?

“In music, these “models” often show up as artists who go viral, artists who chart, the people our peers admire, or the ones the industry puts on a pedestal. The “objects”, the things you start chasing because they’re chasing them are things like virality, stream count, big playlist placements, festival slots, etc. on.

So you might find yourself starting to imitate their moves: adopting their sound, copying their aesthetic, following their release strategy, even pursuing the same collaborations or producers they worked with. Which is not necessarily a bad hting, you just have to step back and ask yourself if it’s right for you. Make sure that you’re not just fitting into a mold, hoping that if you do what they did, you’ll get what they got.

David Bowie warned against exactly this:

“Never play to the gallery. I think it’s terribly dangerous for an artist to fulfill other people’s expectations. They generally produce their worst work when they do that.”

The Danger of Proximity

Girard made a crucial distinction between types of imitation. When you admire someone distant and unattainable (a Beyoncé or Taylor Swift, a legacy artist), there’s a certain safety in that. Their success feels like a north star, not a measuring stick.

But when the model is close to you (an artist at your same level, someone you came up with, a peer who just landed a sync or got playlisted), the dynamic changes. Suddenly, their success feels like it could have been yours. It should have been yours. The proximity makes the comparison feel achievable, and therefore more destabilizing.

This is where mimetic desire becomes most psychologically dangerous for artists. It’s rarely the superstars who shake your sense of self. It’s the peer who seems to be pulling ahead.

Noticing Rivalry Before It Takes Root

This part is uncomfortable but deeply human: when you find yourself imitating someone close to your own level, you can start to resent the very person you’re modeling yourself after.

The music community is, for the most part, deeply collaborative. But that doesn’t mean these feelings don’t arise. If you notice a flash of bitterness when a peer announces good news, or a subtle urge to diminish their win, that’s worth paying attention to. Not to judge yourself, but to recognize it for what it is: a signal that you’ve started measuring your path against someone else’s.

Awareness is the antidote. The moment you see the pattern, you can choose differently: acknowledge the envy as inspiration and fuel, then ask yourself a clarifying question.

If I knew everything this person sacrificed or endured to get here, would I actually choose that path?

Sometimes the answer is no, which reveals the envy was never about your path. Other times, the answer is yes, and the envy becomes fuel, showing you where you could push harder. Either way, the clarity is humbling. And it lets you celebrate their success without letting it destabilize your own sense of direction.

Pop Music Through a Mimetic Lens

Pop music runs on reinforcement loops: charts reflect momentum more than meaning, TikTok pushes what feels familiar instead of what’s visionary, and labels invest heavily in whatever has already proven profitable. It creates an environment where imitation is rewarded before innovation gets a chance.

Radiohead’s Thom Yorke put it bluntly:

“Music that repeats what you know in ever-decreasing derivation, that’s unchallenging and unstimulating, deadens our minds, our imagination, and our ability to see beyond.”

In that world, it becomes easy to let metrics define your value: “My videos aren’t getting enough views, so maybe my music isn’t working.”

This isn’t a personal flaw. It’s just a predictable psychological pattern, amplified by platforms designed to keep us posting, comparing, and adjusting ourselves to what already performs well.

Even Adele had to resist this pull:

“If everyone’s making music for TikTok, who’s making the music for my generation? I don’t want 12-year-olds listening to this record. It’s a bit too deep.”

Even a huge star like Adele had to resist the pull to tailor her music to trendy platforms or teenage demographics. That resistance is itself a rejection of mimetic desire: choosing emotional depth over virality, authenticity over algorithmic approval.

This system can quietly pull you away from the voice that makes you unique. Social media rewards quantity over quality because quantity keeps platforms profitable, not because it makes your art better.

A true artistic ethos values depth, not constant output.

The Alternative: Self-Directed Desire

Girard believed that simply recognizing mimetic desire is the first step out of it, just like Eastern philosophies teach that awareness itself becomes the antidote. We can’t change the world around us, but we can control how we respond to it.

When you feel envy, take a moment to acknowledge it as a sign of inspiration and fuel.

For you as an artist, that choice looks like returning to:

Your taste

Your voice

Your emotional world

Your curiosity

Your internal standards

Your craft

This isn’t about rejecting pop or commercial success. It’s about rooting your direction in intention rather than imitation.

Art built from authenticity has a clarity to it, and that clarity is what lasts.

Closing Thought

The industry moves fast. Trends shift overnight.

In the middle of all that noise, ask yourself honestly:

Why am I making music in the first place?

There is no wrong answer, and it can be as simple as:

“Because it excites me.”

“Because it helps me heal.”

“Because it’s mine.”

Your music is something only you can create. At its core, it should always begin with you. Keep returning to that truth, and build from there.

Your strongest work will always come from the intention that made you an artist in the first place.

What are your thoughts? What’s one thing you’ve stopped doing (or started doing) because you realized it was driven by comparison rather than genuine desire?

A Hesse quote to mind “I wanted only to live in accord with the promptings which came from my true self. Why was that so very difficult?” Thank you for the reminder that it’s possible 🥹